Cosa ne pensa questa traduttrice [scroll down for English] dell’uso dell’intelligenza artificiale per tradurre un’opera letteraria? Funziona?

L’intelligenza artificiale è uno strumento molto potente e sviluppi recenti hanno migliorato molto la qualità delle traduzioni. Ma, personalmente, non credo che sia una buona idea per un autore—che ha investito anni di lavoro e ha revisionato e revisionato ancora il suo manoscritto—di gettare sua opera nel buco nero dell’IA aspettandosi di riavere in mano il suo romanzo in un’altra lingua, pronto per essere commercializzato o proposto a una casa editrice.

L’intelligenza artificiale ha difficoltà nel percepire le sfumature di una lingua e di trovare la giusta forma in un’altra. Non può sentire una lingua e una cultura sulla propria pelle perché pelle non ne ha. Non interagisce con te come fa un traduttore umano. Non ti chiede spiegazioni. Non ti fa domande sulle caratteristiche nascoste del tuo protagonista. Non ti dice che un passaggio non è chiaro per il lettore. Non ti fa notare un piccolo difetto nel testo che va corretto anche nel testo originale.

È vero che l’IA è di grande aiuto nel controllare l’ortografia, la grammatica e la sintassi, proporre possibili approcci a un passaggio molto complesso, e velocizzare le ricerche di un traduttore attento per capire meglio il contesto, l’epoca storica e l’ambientazione del romanzo che sta traducendo. Ma tu, caro autore, sei umano e credo che ci voglia un umano per tradurre il tuo lavoro.

Quando un traduttore di madrelingua revisiona un testo tradotto dall’IA, il rischio più grande è che—dopo un po’—non riesca più a distinguere la voce di IA da quella naturale dell’autore umano. In questi casi, il traduttore deve procedere a rilento, è tormentato da dubbi costanti e lotta per entrare in sintonia con l’autore. Un traduttore professionista fa di tutto per preservare la voce dell’autore, non appiattirla.

Io non vedo l’IA come un nemico ma piuttosto come uno strumento. Uno strumento come un vocabolario online, un computer, o un’app che converti la voce in testo che, insieme, aiutano una persona a produrre qualcosa di creativo e di impatto.

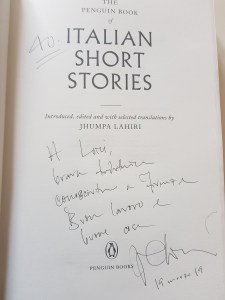

Il mio consiglio per la traduzione di un testo letterario è di scegliere un umano, non una macchina.

What does this translator think of using artificial intelligence to translate a work of literature?

AI is a very powerful tool and recent developments have greatly improved translation output. But, in my opinion, it’s not a good idea for an author—who’s perhaps spent years writing, and revising and revising again a manuscript—to toss it into the black hole of AI expecting to get back their novel in another language, ready to be marketed or proposed to a publisher.

It’s difficult for AI to perceive the nuances in one language and find the best corresponding form in another. It can’t feel a language and culture on its skin, because it doesn’t have skin. It won’t interact with you like a human translator will. It won’t ask you for explanations. It won’t inquire about your protagonist’s hidden qualities. It won’t tell you if a passage isn’t clear for the reader. It won’t notice small defects in your text that should be corrected in the original.

It’s true that AI is a great help in checking spelling, grammar and syntax, and can suggest different approaches to a very complex passage and speed up a careful translator’s research about the context, historical period, and setting of the novel they’re translating. But you, dear author, are human, and I believe it takes a human to translate your work.

When a mother tongue translator revises a text that’s been AI translated, the greatest risk is that—after a while—they can’t distinguish the AI voice from the natural human author’s. In these cases, the translator proceeds at a snail’s pace, suffers from constant doubts, and struggles to connect with the human author. A professional translator does everything they can to preserve the voice of the author, not to flatten it.

I’m not saying that AI is an enemy, but rather let’s keep it as a tool, just like an online dictionary, a computer, or a voice-to-text app which, together, can help a person produce something creative and impactful.

My advice for the translation of a literary text: always choose a human translator, not a machine.